|

| Diaphragm Seal courtesy of AMETEK U.S. Gauge |

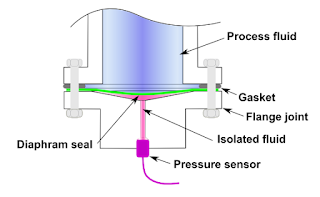

In the operating principle of the diaphragm seal, the chamber between the diaphragm and the instrument is filled with system fluid, allowing for the transfer of pressure from the process media to the sensor being protected. The seals are attached to the process by threaded, open flange, sanitary, or other forms of connection. The seals can also be known as ‘chemical seals’ or ‘gauge guards’. Stainless steel, Carpenter 20, Hastelloy, Monel, Inconel, and titanium are used in high pressure environments, and some materials are known to work better when paired with certain chemicals.

|

| Diagram of diaphragm seal (courtesy of Wikipedia) |

Sanitary processes, such as food and pharmaceuticals, use diaphragm seals to prevent against the accumulation of process fluid in pressure ports. If such a buildup were to occur, such as milk invading a pressure port on a pressure gauge and spoiling, the quality and purity of the fluid in the process may be compromised. Extremely pure process fluids, like ultra-pure water, could be contaminated by the metal surface of a process sensor. Pneumatic systems rely on the elimination of even the smallest pressure fluctuations, and diaphragm seals prevent those by ensuring the separation of the process materials from the sensors.

|

| Diaphragm seals protect the sensors on pressure switches like this United Electric Controls model. |

For more information on diaphragm seals, visit Ives Equipment at http://www.ivesequipment.com or call (877) 768-1600.